George Chinnery, an established British painter, disembarked from the ship Hythe in Macao on 29 September 1825 following a lengthy two-and-a-half-month voyage from Calcutta, India. Rumours ran rife that he went on a retreat to the south China coast for health reasons. He claimed, perhaps half-jokingly, that he ventured to such a faraway place to escape the confines of married life. But the truth was that the heavily indebted painter was desperate to seek, if not a fortune, refuge from his many creditors. Never did he imagine that he would spend the rest of his life immortalising the beauty of Macao, with his drawings revered as masterpieces, which showcase a rich tapestry of the cityscapes and everyday life in the Portuguese enclave before the advent of photography.

Over the next 27 years, until his death in 1852, Chinnery worked obsessively and prolifically, producing thousands of drawings and sketches of buildings and people in the City of the Name of God. It was not uncommon to bump into him at the crack of dawn, when he would wander around thoroughfares, alleys and beaches to make sketches of anything that interested or amused him. Using Thomas Gurney’s shorthand system, he would annotate the margins of his sketches with pencilled notes, briefly reminding himself of what he might need to follow up on the outlines for finished works. In addition to being personal reminders, such iconic notes contain astute observations and comments that offer a glimpse into Chinnery’s artistic mind. For example, a page filled with drawings of Chinese figures, dated 24 March 1849, bears a shorthand remark, “It is the power of extracting the poetry from the prose of all objects in nature that constitutes the genius for both poetry and painting.”

While the era of Tanka (蜑家) boatwomen ferrying passengers around in egg-shaped sampans is long gone, some places painted by Chinnery have remained virtually unchanged over the past two centuries, the most notable of which is A-Ma Temple. In his drawing dated 27 June 1833, the temple is depicted on the waterfront with lush greenery that enthrals the viewer immediately. Nearby lie some boulders, a sea wall and a tall flagpole, with traditional sampans berthed in shallow water outside the temple. A-Ma Temple has stood the test of time, retaining its vibrant charm. Despite now being located a bit inland, the temple keeps its allure of tranquillity and prolific greenery to enchant visitors and artists. Its prayer halls and courtyards on a cascading rocky hillside provide a picturesque setting that has captivated generations.

Another example of Chinnery’s artistic legacy is his drawing of the Ruins of St. Paul’s dated 18 October 1834, showcasing the grand facade of Mater Dei Church accessible by a long flight of steps. Next to it stands St. Paul’s College founded in 1594 by the Jesuits, the first western-style university in the Far East. A few months later, however, the church and the college were reduced to heaps of ashes in a conflagration, except for the church facade, which survived the blaze and was captured by another Chinnery drawing dated 3 August 1835. Renowned for the magnificent facade adorned with a fascinating array of western and oriental sculptured motifs and Chinese inscriptions such as “聖母踏龍頭” (“St. Mary stepping on the head of the dragon”) and “鬼是誘人為惡” (“The Devil tempting men to commit evils”), the Ruins of St. Paul’s has since then become a landmark tourist attraction and the pride of Macao, embodying the cultural melting pot that defines the city.

With his paintbrush in hand, George Chinnery set out to capture the vibrant tapestry of life in Macao, portraying the settlement as a lively and dynamic community. He sauntered through the streets and public places—from the esplanade on Praya Grande to the bustling market outside St. Dominic’s Church in Largo do Senado—immersing himself in sketching the daily lives of individuals from all walks of life. The exotic cityscapes provided him with an abundance of compelling subjects to depict: street vendors, stonemasons, blacksmiths, boat dwellers, gamblers and beggars. Interestingly, the wealthier Chinese, Parsee traders and upper-class European gentlemen and ladies, who typically commissioned the painter for individual portraits, were largely absent in the street scenes of his drawings.

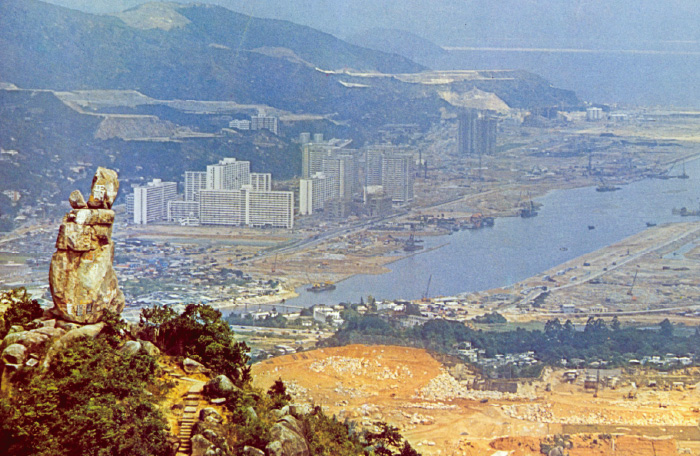

The past two centuries have witnessed a profound transformation of Macao from a modest trading outpost into a casino hub. Had Chinnery lived now, he would have scarcely recognised this bustling hub where he had spent decades painting, even unto the end of his life. He might not have found a fortune in the Orient, but he left behind a remarkable legacy of artistic wonders, giving us a glimpse into a world long gone.