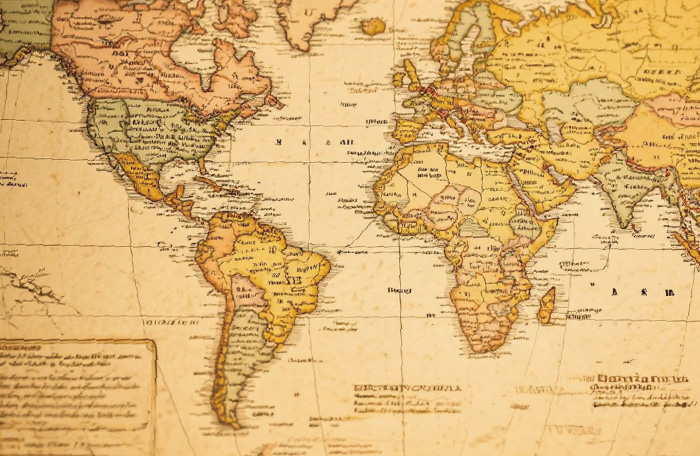

For most people, maps are nothing more than direction guides and navigation tools. But for history aficionados, maps can reflect, reinforce and reshape contemporary views and ideas, bringing big changes to our world. It is this argument that Jeremy Harwood interrogates in his fascinating book To the Ends of the Earth: 100 Maps That Changed the World.

Deeply inspired by the wonders of nature, our ancestors expressed through maps their imagination and fascination about the origin and nature of the universe. Let’s take a look at the Babylonian Map of the World, one of the earliest surviving maps. Inscribed on a clay tablet from as early as 2 800 years ago, the map depicts ancient Mesopotamia as a disc floating on an ocean. The city of Babylon is represented by a rectangle near the centre of the disc. The outer islands marked as triangles outside the disc were believed to be beyond human reach. The cuneiform inscriptions on the back of the tablet reveal that they were “islands of transition”. Based on key phrases like “perpetual darkness”, “brighter than sunset or stars” and “horned bull”, we can conclude that the map undoubtedly captures the cosmological views and religious beliefs of the Babylonians.

Such a linkage between cosmology and cartography is far from unique in ancient civilisations. The ancient Egyptians applied their cartographic skills to portray mythical worlds and produce lavish maps on sarcophagi. According to the Book of the Dead, it is of paramount importance that the deceased follow the right path to resurrection. Elaborate routes painted on coffins would therefore navigate the dead to the underworld to appear before Osiris, the god of the afterlife, to gain a chance of rebirth in the next life.

In addition to conveying cosmological views, maps can disperse knowledge and provide a representation of the world. A notable example is the largest extant medieval map, the Hereford Mappa Mundi created in England circa 1300. Drawn on a single sheet of vellum some 130 cm in diameter, the map provides information on locations of cities and towns such as Rome and Hereford, and also presents a kaleidoscope of Bible stories, myths, legends, as well as strange beasts and peoples of the world. For instance, there is a clear passage through the Red Sea shown on the map, telling the Bible story of the Exodus of the Israelites to the Promised Land after 400 years of slavery in Egypt. A cartographic masterpiece in all times, this map shows the history, geography and destiny of humanity as it was understood in Europe at the turn of the 14th century.

During the Age of Discovery of the 15th and 16th centuries, maps recorded explorations and discoveries of new lands by adventurers and seafarers. They expanded the world on one hand and contracted it on the other by making faraway lands seem more accessible. In 1502, an Italian agent in Lisbon called Alberto Cantino paid a cartographer to copy a map from the Portuguese hydrographical office, and secretly brought it back to Italy. The Cantino Planisphere, the smuggled chart, presented an informative and up-to-date report on all the Portuguese discoveries, depicting the coasts of South America, Africa and India with awesome accuracy. It was jaw-dropping, given that Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope only in 1497 on his historic voyage to India. This world map helped convince those in power in Lisbon that it was feasible to claim the newly found lands, ushering in the further explorations of trading routes that ultimately led to Macao in 1513.

Maps are not always as objective as they appear. When used for propaganda purposes, they can be manipulated to influence or shape people’s views. The Christian Knight World Map created by the Protestant Dutch mapmaker Jodocus Hondius in around 1596 provides a classic example of cartographic propaganda. Made in the middle of the Eighty Years War when the Protestant Netherlands was fighting Catholic Spain for independence, the map depicts an allegorical scene at the bottom where an armoured Protestant knight fights evils like vanity, sin and death, all symbolically associated with Catholicism and Spanish adversaries at that time. It is also believed that the face of the knight was drawn to resemble the king of France, an ally of the Protestants.

While these examples show the use of maps to reflect cosmological and world views, disseminate knowledge and advance territorial claims, there are other instances that maps have been used for the betterment of society. For example, the British social reformer Charles Booth pioneered in commissioning maps to chart poverty and wealth in late 19th century London. The findings were by any measure appalling: 35 per cent of Londoners were living in poverty. Surprised by the severity of poverty, he became a strong advocate of state pensions for the elderly, which eventually came into effect in 1909.

The assertion that the 100 maps in Harwood’s book changed the world is open to debate. Yet, maps indeed open windows into the past and provide the instruments for understanding the present, allowing exploration in the uncharted territories of tomorrow.