On 6 September 1992, several Alaskans found a disturbing note taped to the door of an abandoned bus deep in the Alaskan woods. Scribbled on a page torn from a novel, it read:

s.o.s.

august ?

Inside the bus was the emaciated body of Chris McCandless himself, a 24-year-old honours graduate who had been on a quest for solitude and self-realisation in nature. How this brilliant and idealistic young man with a promising future came to his demise is revealed in Into the Wild, a compelling book by Jon Krakauer. In a riveting narrative, Krakauer takes readers from the tragic moment of the discovery of McCandless’s body back through his childhood, ascetic renunciation and icy withdrawals that marked his passage into adulthood, and, in vivid detail, the two years of restless wandering to his final journey to the Last Frontier.

Chris McCandless came from an affluent family in Washington, DC. He was very intelligent, a top student, an elite athlete and a talented musician. Yet domestic violence and bigamy lurked behind an ostensibly privileged upbringing. As McCandless’s resentment towards his parents grew, so too did it towards the superficiality of bourgeois life. Influenced by writers such as Jack London and Henry David Thoreau, McCandless developed a strong interest in communing with nature. Immediately after graduating from Emory University in 1990, he severed all ties with his family, donated his law school fund of more than US$24,000 to charity and took to the road. When his car was stuck in a flash flood at Lake Mead, he stripped it of its licence plates, burned all his cash and buried most of his possessions. He gave himself a new identity—Alexander Supertramp—and began his life as a tramp.

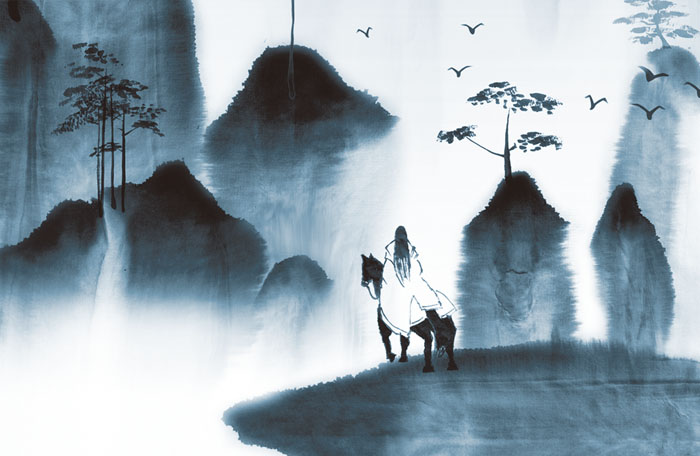

In a haphazard way McCandless roamed through the Southwest walking, hitchhiking and jumping freight trains. He canoed down the Colorado River all the way to Mexico, tramped up and down the Pacific coast and into Montana. Along the way he worked in an Italian restaurant in Las Vegas, flipped hamburgers at a McDonald’s, and took on dirty and tedious jobs on a harvest crew. In hitching rides, he bonded with rowdies, hippies and other vagabonds, who would become his greatest friends and confidants. Through Krakauer’s engaging and unpretentious depiction of these people, the book paints a candid portrait of America’s communities of outcasts and eccentrics.

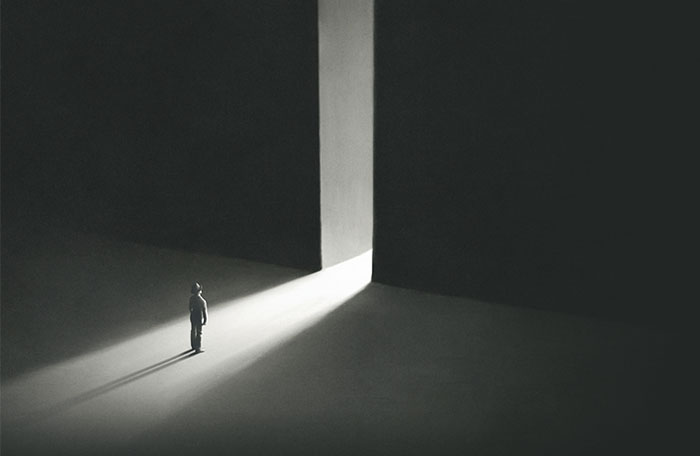

Eventually, in his pursuit of raw, transcendental experience out in the wilderness, McCandless set off on his “last big adventure”. After waving goodbye to a trucker who had given him a lift and a pair of rubber boots on 28 April 1992, he walked alone into the treacherous Alaskan bush with a rifle and a backpack, which contained little more than books, some cooking utensils, a sleeping bag and ten pounds of rice. He survived 113 days before succumbing to starvation, aggravated by ingestion of poisonous wild potato seeds.

Krakauer’s protagonist has garnered polarising opinions among readers. Some laud McCandless as an inspirational figure who broke free from the establishment and embraced the natural world in the most authentic and adventurous way. Others regard him as a reckless and arrogant fool who brought doom upon himself. “He’s this Rorschach test: People read into him what they see,” Krakauer admitted in an interview in 2016. “Some people see an idiot, and some people see themselves. I’m the latter, for sure.” He sees a lot of his younger self in McCandless. Like him, Krakauer has an autocratic father and feels the same infatuation with nature. He devotes two chapters to his own near-fatal solo ascent of the Devils Thumb, one of the most dangerous mountains in Alaska. Krakauer draws on that experience, along with stories of other ill-fated adventurers and McCandless’s letters, journals and annotated books, to explore the essential impulses that drove McCandless to his destiny.

In his last days, McCandless took a photo of himself holding a farewell note that read, “I HAVE HAD A HAPPY LIFE AND THANK THE LORD. GOODBYE AND MAY GOD BLESS ALL!” His face was horribly gaunt, but he was smiling, looking contented with the shining eyes of one who had lived his dream and was at peace. Did McCandless find what he was looking for? Were the experiences worth a life cut short? We might never know the answers to these questions. What is certain is that his story has captured the hearts and minds of people around the world. McCandless may have died young, but his legacy will live on.